Howdy folks!

This is long overdue, but a looooooot of stuff got in the way.

First thing’s first, play the game here. You can view the source code for all of what I’m about to discuss here

And as some optional reading, you can check out how we did it for the year prior.

The New System

Using Unity for the first year… kinda sucked. There was no good way to ensure consistency between exported projects, which was the main problem. Because of this lack of consistency, a lot of time was spent debugging, fixing the framework, and updating the extension to make sure everyone’s games could sorta work okay.

Never again. The new system has to (on top of switching between games and passing information back and forth between them):

- Keep game information contained and separate.

- Basically like a bunch of virtual machines. So we don’t have ANY overlap between games and we don’t have to tweak settings per-game so that the whole build looks okay.

- This is the most important thing, because otherwise it means a lot more debugging work for the system.

- Ensure builds are consistent.

- If anything goes wrong with building the game, it should NOT be our system’s fault. It’s all up to the developers and how they make their games.

- This doesn’t just include where the games are building to, but also that they all have the same display resolution.

- Be as low-maintenance as possible.

- So again, if something goes wrong it’s less likely to be our system.

- If this works right, it means we don’t have to touch or debug the games. It’s more of the jammer’s fault if something goes wrong.

So, there were two possible ways I saw of going about this. Either:

- Build to HTML/JS

- HTML/JS/WASM and/or WebGL is widely supported by practically every popular game engine and web browser under the sun.

- Slower performance for resource-heavy games (which is actually desirable for encouraging Microgames)

- Build to a standardized format in say, Unix to get Docker (or something similar) run the games.

- Adds a lot more support for game engines, since making an executable is theoretically easier.

- Much harder to set up.

And I’m sure I would have pleased a lot of nerds if I went with the Docker solution, since it could be argued to be cooler and more interesting. And I know that web browser games have a reputation. Javascript and HTML especially. But I’m a developer, and I get to choose what frameworks I want to use. And I’m not going to make more work for myself just to score nerd credit. Plus, I think we ended up doing some pretty cool stuff here. Let me break it down.

Iframes

HTML has the magic solution already. iframes. This just tells your browser to run another webpage inside of the one you’re already in. Now, browsers are very persnicketty and panicky about iframes since you can theoretically use them for malicious purposes if the stars of web security don’t align just right. So there are a lot of restrictions on how and why you can use iframes, and a lot of that can depend on the server you’re running.

In my testing on itch.io though, I discovered that as long as you package all the games into one folder, then the server and the browser don’t freak out about Cross Origin Resource Sharing.

So we can display games. Now we just have to communicate with them.

Game Interface

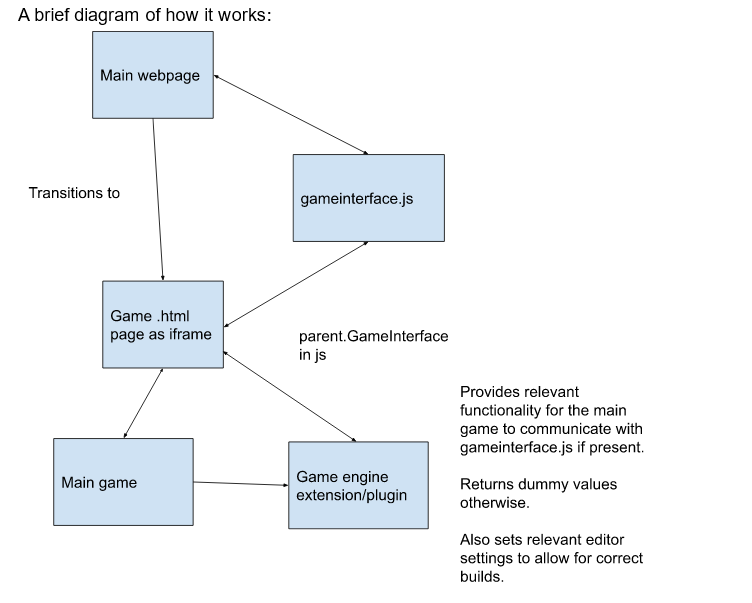

A lot of game engines actually support being able to execute code in the browser for builds, and that’s very useful indeed. And even if they don’t, as long as they build to web it’s still very much possible to rip out the guts and hack together something that functions similarly (it takes a lot of work, but it’s theoretically doable).

So, if we let the games be the ones to grab information from the overall game manager, then we have a solution that checks pretty much all the boxes we need for this solution. We can just build a singleton (or a close approximation of one) in the browser for each game engine to access with a custom-built extension or plugin we can provide to each of the jammers. And that’s it!

gameinterface.js is the main component for interacting with the games. It communicates between the framework and is called by the games to act as the source of information for:

- The number of lives

- The current difficulty

- The time left

- The function to win the game

- The function to lose the game

- The function to start the game (should be called by the extension, not anything else)

- This is a requirement, since we need to know when the game is loaded. Unfortunately, it makes this just the tiniest bit harder to test.

- The function to set the max timer for the game

- A few other construction functions for setup that the extensions don’t really need to access (so they don’t)

And that’s it! The overall manager itself is expected to do management things like switch between games and automatically lose if time runs out (this code is in version-style.js due to poor decision making on my part. We’ll get to that in a bit).

PICO-8

PICO-8 was interesting to build an extension for because it doesn’t necessarily have Javascript code execution built-in. HOWEVER! PICO-8 aims to simulate a console, and so has virtual “pins” that you can use both in PICO-8 and access from Javascript. So we just need one extra script (picointerface.js) on the browser side to detect if PICO-8 is running and communicate back and forth between the game interface.

Bringing it all together

There’s an HTML page that runs all these Javascript files in the background. All it has to do is let the user play the games, and handle loading between them.

So, this wasn’t all that hard to set up, and there’s actually some documentation of how the system works. Check it out if you’re so inclined: https://gdacollab.github.io/Microgame-Jam-GHGT-Framework.

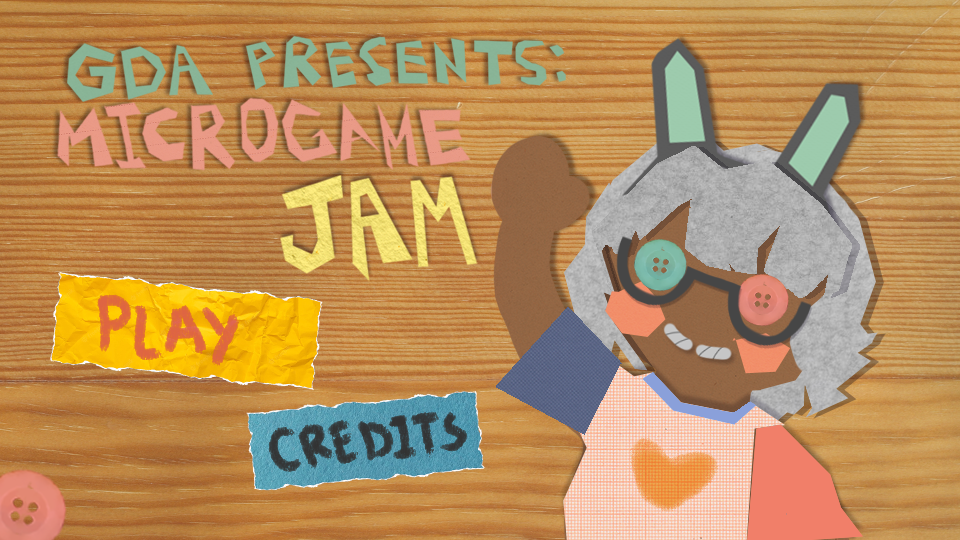

After this part was finished, the only remaining piece is in making the user-facing piece to let them play these games. And it should look pretty too.

Making the front-end

So yeah! We cranked out the extensions over the summer, and the rest of the work had to be making sure that the web framework around everything would work just fine.

This is where we really overshot in terms of scope. Because the framework had too much going on. I wanted controller support, customizable settings, smooth transitions, cool looking animations, a bug-free experience. That just kept adding on to how much time it would take to do everything. The successive loading of iframes wasn’t hard to implement, so let’s talk about each additional piece:

config.ini

The backbone for rendering the HTML, and probably the worst part of this project. I was not thinking when starting this out, and I did not revise as soon as I realized it was a problem, because by this point we were too far in to stop. Basically, there’s a file. config.ini. It contains literally ALL of the assets the framework needs to display properly. Animation images? Button sprites? Menu layouts? Game folder locations? ALL in config.ini.

It isn’t even packaged ahead of time. This thing is loaded in real-time for the build. WORST decision I’ve made for this project. I am deeply, terribly sorry to everyone who is stuck with it. I want you all to do better.

For anyone looking to make revisions, or for future reference: webpack, typescript, any step of Javascript or HTML where there’s a compilation process, you could do with that instead of this. Hell, add a shell script if you need to. Just anything to avoid loading these images on the fly. The issues don’t just extend to setup though. Let’s take a look at those animations.

CCSS

Let’s take a look at these animations:

Wow, are they gorgeous. Absolutely beautiful.

By far the longest things to get right were CSS animations. One of our artists, MetaToshi made some amazing animations. Here are the originals for context (warning, sound):

You may notice some differences. That’s because I had to translate these animations into CSS by hand. What I should have done was set up a system for exporting animations from Blender or Adobe Animate into CSS (or found a tool that did the equivalent). But I fell victim to the classic programmer’s fallacy: I made a cool system that I really, really wanted to use.

You see, CSS animations don’t allow for neat timelines. You’re allowed to specify a start and a duration. That’s about it. So how do you translate a well-timed keyframed animation into CSS? If I had used something with a compilation step (again, Webpack, Typescript, etc.), I would have used something like SCSS/SASS and a plugin for proper coordination. But I didn’t want to add more libraries or setup steps for just one aspect of the project. So I made a system that I called CCSS. Which is a meaningless acronym, it doesn’t really matter what it stands for. Here’s how it works though:

- Attach a Javascript class to a CSS file. Call this class “GlobalAnimationManager” or something.

- Have that Javascript class read everything in that file, looking for specific variable names under specially marked CSS animations.

- Each CSS animation can have a variable that points to ANOTHER CSS animation, with information about when during the current animation playback that animation should start, how long it should last for, etc.

- Store all that information in separate CSSAnimation JS classes, and run all of these in realtime.

It’s a cool system because it gives you some control over a timeline of animations, but ultimately bad because it’s just not that good. It requires Javascript to do a lot of heavy lifting, both in initialization and when animations are playing. It means that if there’s say, a lot of lag, then the animations will get out of sync. It’s a nice system in theory, but not great in practice.

In addition, the way that animations are done means that you have to set up every single piece that you want to be animated during a transition in config.ini. So it’s a lot of going through .CSS and .ini files to set everything up how you want. Definitely not easy to use.

Main Menus

The main menus also use CCSS, but mostly for transitioning between different screens.

The great thing about the main menus is that they have controller support. And I did a lot of work to emulate key presses from controller input. There’s even re-bindable controls. Honestly though? Probably not worth it. I don’t really know anyone who played the games with a controller, and as fun as it was to set up, it probably would have been more worthwhile to focus on other parts of the front-end.

Security Risks

Yeah, so just passing games control of browser execution is not a great idea. If you were hoping to make a gigantic game jam and collect everyone’s games to automatically compile into one big game… probably a bad idea. It’s still the same amount of risk you might see on itch.io (or other game distribution sites) for people publishing viruses. But still. If this is something you’re interested in doing yourself, do it with people you trust.

Lessons Learned

Let’s take a look at our design goals and evaluate how we did:

- Keep game information contained and separate.

- This worked beautifully. The extensions did their job in communicating between the game and the frontend really well.

- Ensure builds are consistent.

- This was a hard measure to ensure, but nearly everyone came through. We reached out to anyone who didn’t submit their games.

- Be as low-maintenance as possible.

- For the extensions, this works really well. We hardly have to touch them for future versions.

- For the front end, it requires a re-write every time there’s a theme change. Not good.

The backend system works beautifully. I spent a lot of time working on that over the summer and designing it to be as smooth as possible, so I cannot complain there. Most of this blog focuses on the front end, however, because I feel that it’s where most of the critique should go. The user experience was sort of forgotten about, and while the current build handles that well, potential future designers and programmers are stuck with a sloppy system for improvements. I’m glad that I got the iframe system working, and I encourage future people to use that. But when it comes to the front end, feel free to throw it out and start over.

Thanks for listening! My next blog post should hopefully be about the improvements I’m making to The Jackbox Party Pack 7 Custom Content (soon to be renamed). It’s currently all being re-written in Rust, and expect something… I dunno. Spring 2024?