Hello, and welcome to this explanation of how the racing system for Gremlin Garden works. If you haven’t played Gremlin Garden already, you should. It’s got literally everything you could ever want out of a game that has the wild combination of gremlins and gardens.

Now, I did do a lot of miscellaneous programming for Gremlin Garden, but the main thing I worked on was the entirety of the races.

The Basics

Well, not the entirety. A huge debt of gratitude goes to the Bézier Path Curve tool by Sebastian Lague. Without it, the workflow for creating races would have been so much more complicated.

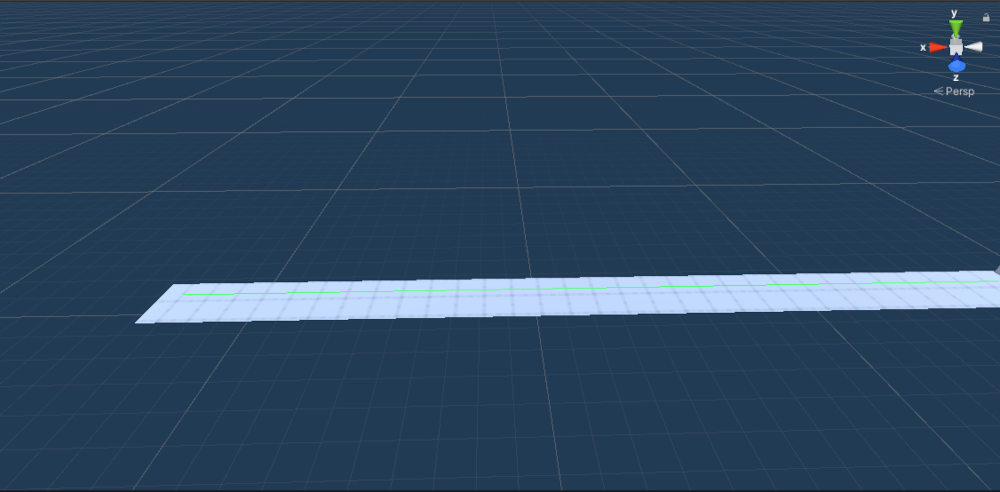

In its most basic form, the way that gremlins race in Gremlin Garden is that they simply follow a pre-constructed path made using the Bézier Path Curve tool. So a basic racetrack would look something like this:

It may not be entirely obvious to you, but a race is more than just lines. It’s how fast or slow something is going on those lines that makes a real race. Each gremlin in Gremlin Garden has a stat that influences how fast or slow they move along our pre-constructed paths. There are also specific animations and particles that appear on certain segments of each race, and separate QTE prompts.

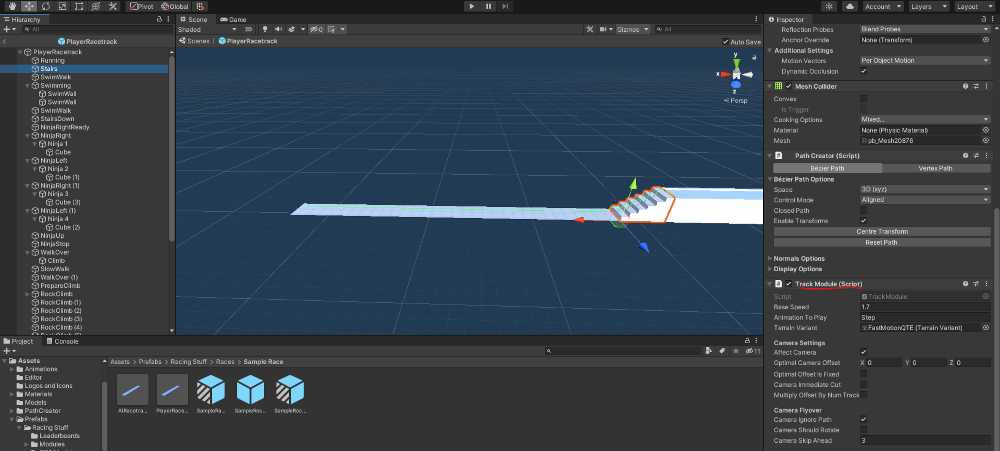

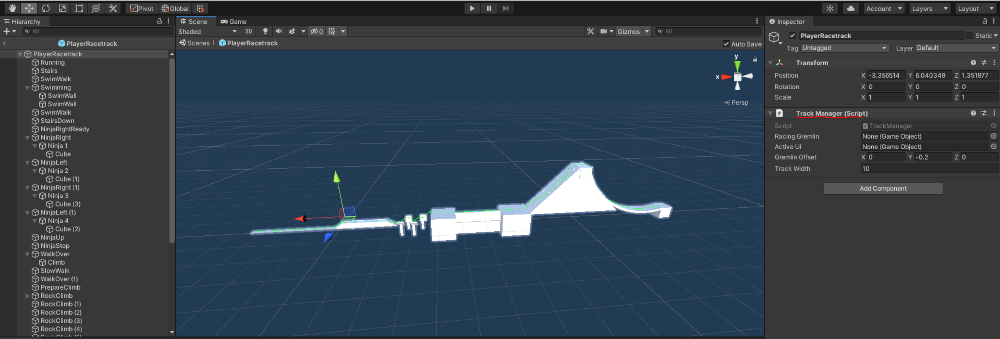

In order to make a gremlin’s actions dependent on the type of path they were currently racing on, I divided each part of the track into sections. Each section is composed of a path and a “Track Module” component. The Track Module component is in charge of moving the gremlin it is assigned along the path. The Track Module will also do things that are specific to this part of the race, like showing a certain QTE prompt, displaying different particle effects, or slowing/speeding up the gremlin based on the gremlin’s stats.

Each Track Module is also parented to a Track Manager object. In simplest terms, the Track Manager tells the gremlin which Track Module to be on.

To slow or speed up gremlins based on their statistics, each Track Module has two variables: a base speed (which can be adjusted by the designer), and a modified speed (which is calculated by the Track Module based on the gremlin’s stats). The base speed is how fast a gremlin is supposed to move on that Track Module with average stats.

The modified speed is simply a percentage of how much to move the gremlin derived from the base speed. So if the modified speed is 100%, then the gremlin moves 100% of the base speed. If the modified speed is 50%, the gremlin moves at 50% of the base speed. I also didn’t know if art would be able to come up with animations for gremlins at different speeds, so the modified speed also gets applied to the speed of a gremlin’s animation. So at lower modified speeds, you’ll see your gremlin have a slower movement speed AND animation time.

Here’s an early prototype of all these systems in place.

Cylinder Ninja Warrior pic.twitter.com/Hkxm4EwKNK

— Tyler K (@ambiguousnames) January 17, 2021

Okay, but now there’s another problem. I needed a way to set the modified speed based on the gremlin’s stats. The only real obstacle was that design had not told me how a gremlin’s speed would be calculated during races, or if the formula for speed calculation would even use the same formula for every Track Module. So I turned to Scriptable Objects.

Scriptable Objects

In case you’re not familiar with Scriptable Objects, they’re a feature Unity has where you can basically save data in Unity’s editor and share that data across multiple scenes. Changing the data stored in a ScriptableObject means that every script referencing that ScriptableObject will see that data being changed. There’s a much better and in-depth explanation available on Unity’s website, if you’re interested.

So, each Track Module in the game takes a ScriptableObject called a Terrain Variant as input. A Terrain Variant is a ScriptableObject with only one function we really care about:

relativeSpeed, which takes the Gremlin’s data and the current module and returns a percentage. The current version of Terrain Variants also have extra parameters to specify things like what QTE prompt should be used and what particles to play.

The TrackModule then looks at the data the Terrain Variant provides and uses that to modify its own internal variables for a different gremlin racing experience for each new TrackModule.

In this way, the Terrain Variant class allows you to make Track Modules highly customizable. You can slot in the Running Terrain Variant (a class derived from Terrain Variant) into all the tracks that need to calculate the speed for gremlins running, and if you don’t like any one aspect of how the particulars of gremlins running looks, you can change the inner workings of that Running Terrain Variant class, and all the tracks that use the Running Terrain Variant scriptable object will change accordingly.

The only real drawback to using this system is that every time you want to set up the formula for calculating speed for a new stat, you have to create an entirely new C# class from which to create the scriptable object, which isn’t very designer friendly. I still stand by my decision, though. I didn’t have the time (or the need) to set up an entire designer scripting language, and this system allowed designers to pretty easily change track behavior with just a drag and a drop.

And that’s pretty much it. That’s how the races in Gremlin Garden work, and the end result looks pretty good!

If you’re interested, all the code for the Racing system is here.

What I Didn’t Cover (That I’ll briefly cover right now)

Terrain Variants also used to have a function called positionFunction which was used to offset gremlins during animations to make their motion look more believable (like how they might bob up and down when swimming), but most of that was removed (since the animators could add that detail in themselves if they so wished).

There’s two special types of Track Modules, one called an Equation Track Module, and the other called a Tween Track Module. The Equation Track Module treats the positionFunction of a Terrain Variant as an actual equation that sets gremlin position. This is used to calculate how gremlins are supposed to “glide” in the races. I actually made an equation on Desmos to show how gremlin position based on the gliding stat is calculated.

I worked on the whole camera system that gives you the intro to races and does a whole flyby. All it does for the flyby is follow one of the pre-existing paths. For the camera wipe at the end of the race, I just use a second camera to create a texture of the racers that the racing camera looks at before teleporting the racing camera over to the racers. It’s passable, although I wish I had ironed out a few more issues with its behavior (and made it much more object oriented).

I also created an adjustable difficulty system each race that mimics how most people roll for stats in D&D. Here’s the full code (with comments), if you’re interested.

Reflection

Looking back on everything, I have three big regrets:

First is how gliding works. The formula for gliding never actually checks to see if the gremlin hits the ground, it only tries to detect when the gremlin is at the x-intercept for the equation, so I had to do some hacking to get the gremlin to look like it actually had landed before the formula thought it did. If I could go back and do it again, I’d make a formula that actually detects when a gremlin hits the ground.

Second is that I didn’t add more tools for debugging the races. At some points, I was in a rush to fix some aspect of the races, and I regretted not adding tools for easy debugging early on to test specific parts of any race track.

Third is that I didn’t make a “flip path indices” button until the very end. This is probably my greatest shortcoming. The bézier path curve tool does NOT have an indicator to show which point on a path will be considered “first”, so as a result, I saw a LOT of gremlins teleporting and running backwards because the indices of the path array were ordered wrong. I could have fixed most of these problems by making a button to flip how the path indices were ordered, but I didn’t think of that until it was too late.

I guess that’s everything. Thanks for taking the time to read this, and remember that unlike Elephants, Gremlins never forget. Never.