Temper your expectations, it’s disappointing.

For context, we were discussing Jacob Geller’s new video. In that video Geller poses a few key questions about the game Mountain (2014), and they’re ones that we are prepared to answer.

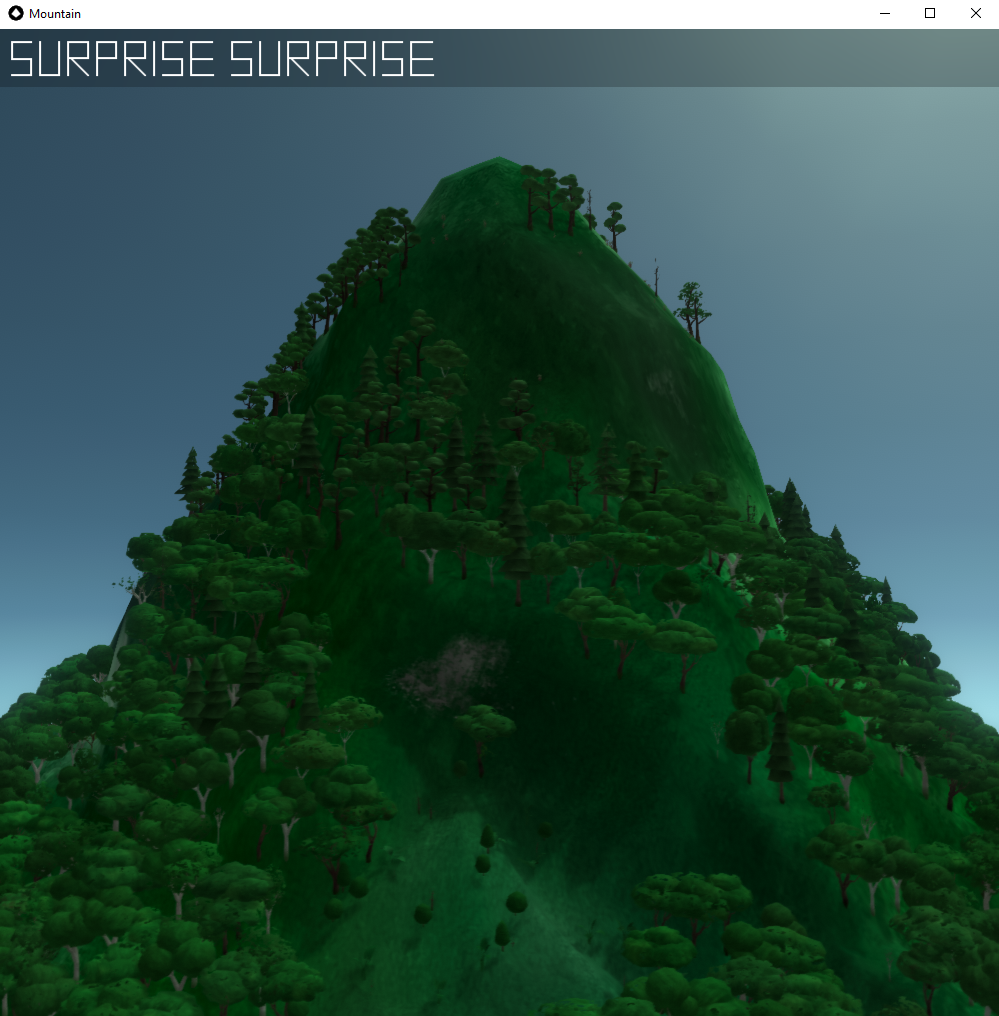

At the beginning of the game Mountain, you’re presented with three drawings. Then a Mountain is made. From that come the questions.

The first question: Is Mountain (2014) actually a game? Go to Mountain (2014)’s steam page, and you’ll see it called an Existential Nature Simulation. On its website, it’s called a Nature Simulation Game. Game Developer calls it an ambient procedural mountain simulator, Killscreen calls it a God Simulator, and Rock Paper Shotgun simply calls it a Mountain Simulator. Its developer, David OReilly, has referred to it as both a Relax em’ up and Art Horror - words that may evoke game-like meaning, but aren’t indicative of actual gameplay.

It seems nobody wants to call it a game (that, or nobody wants to make the executive decision to call it a game). We’re cycling through these descriptors because we’re looking for the words to describe an experience that, even 9 years after release, is novel.

There are a few questions about what makes Mountain a game or not. But there’s a second question that needs answering:

Do the Drawings in Mountain (2014) Do Anything For The Mountain?

Yes. Sort of.

That is to say, when you draw in Mountain, there are indeed tangible effects that you can see happening on the screen for yourself as a result from your drawings. Sort of.

We were able to prove this by decompiling the game’s internal structure. You’re even able to do the same things to come to the same conclusions we did. The only tools you will need are:

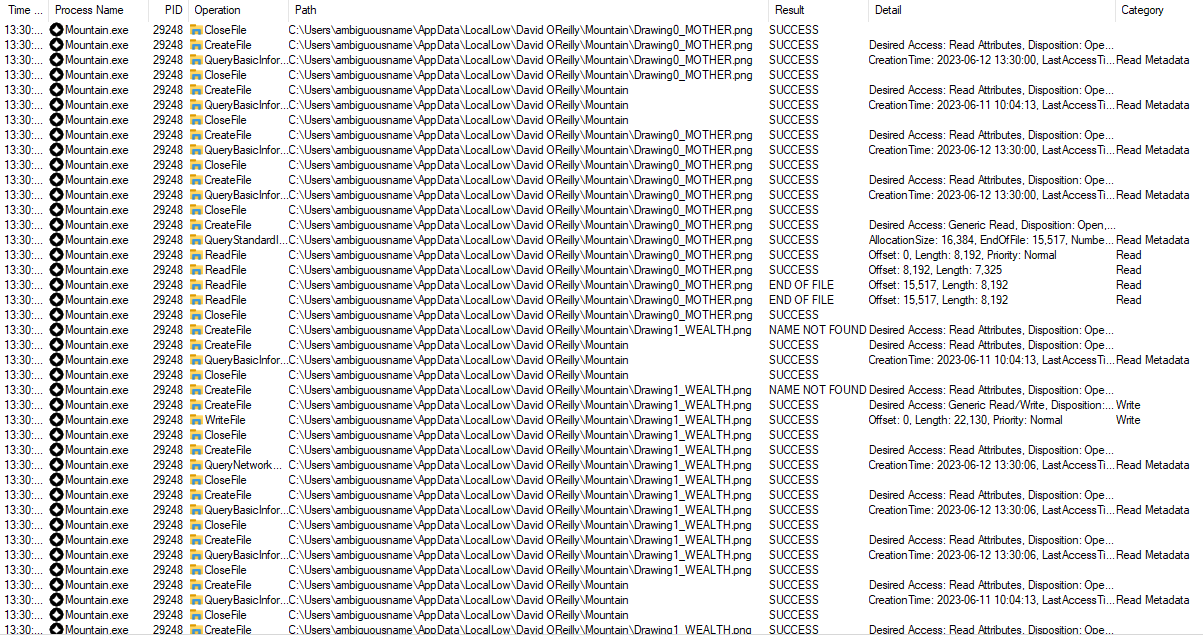

- Some kind of monitor for viewing what your kernel is doing and why. Particularly for monitoring read/write access. On Windows you can use ProcessMonitor.

- ILSpy, for looking at the internals of how Mountain works (since it runs on Unity).

ILSpy is gonna do most of the heavy lifting for us. Once we open Mountain (2014)’s Assemlby-Csharp.dll, we can see everything that Mountain uses in how it operates.

With these tools you can answer the question yourself. And we can even show you how it gets answered. But we have to ask: is there any answer that you would be satisfied with? And what might that be? The drawings of Mountain (2014) are probably the closest you’ll get to meaningful interaction with the game. You can pan the camera, you can play notes, you can unlock achievements. There are cheat codes to make it rain blood. You can make the Mountain say things with certain keypresses, and you can speed up time. Do any of these interactions mean anything to you? Does any of this make it a game? A game that you would enjoy playing?

How does Mountain (2014) Create and Read Drawings?

The thing that stands out most is the class Drawings. This is gonna be what’s storing all of the drawings that Mountain makes. There’s also the class DrawingCapture, which stores the Drawings that you draw at the beginning. Once DrawingCapture gets input from the user that a drawing is done, it will save the drawings to:

%appdata%\..\LocalLow\David OReilly\Mountain1

Finally, the images are loaded BACK in using a combination of the class Drawings, and the CoolStuff.LoadImage function:

// Assembly-CSharp, Version=0.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null

// CoolStuff

using System;

using System.IO;

using UnityEngine;

public static bool LoadImage(string path, Texture2D tex)

{

try

{

if (File.Exists(path))

{

BinaryReader binaryReader = new BinaryReader(File.Open(path, FileMode.Open, FileAccess.Read));

byte[] data = binaryReader.ReadBytes((int)binaryReader.BaseStream.Length);

binaryReader.Close();

if (!tex.LoadImage(data))

{

Debug.LogError("LoadImage failed to load the image data!");

return false;

}

return true;

}

}

catch (FileNotFoundException)

{

Debug.LogError("Loading image failed. " + path + " not found.");

}

catch (Exception ex2)

{

Debug.LogError("Loading image failed: " + ex2.ToString());

}

return false;

}Which to translate, just loads an image from a filepath if the file at the path exists.

Luckily for us, these are the only three classes that we really care about. Although, we feel like we should lay some groundwork to prove that these are the ONLY classes that we should be concerned with. We’ll start with one assumption:

%appdata%\..LocalLow\David OReilly\Mountainis the ONLY place that drawings are saved and loaded from.

This was the only place that we could find the drawings being stored to and loaded from, and we seriously doubt there are any other places where drawings are saved to or accessed from. If you feel like proving otherwise, go ahead. But based on that assumption, the rest of this will be a proof by induction. First, how do we know that CoolStuff.LoadImage is the ONLY function that loads files? Well, we can look at Mountain’s process during start-up and image creation:

We have the same pattern repeated throughout: CreateFile2 called by Mountain.exe, then a QueryBasicInformation, then finally a CloseFile. There’s a whole lot of extra calls here for querying information that we can skip over. Every time the files are opened and closed, there’s only ever one real call to read and then close the file3. That’s at the end when the process is done reading the file and its associated metadata.

And to double check, File.Open (to read the images) is only ever called once by the entirety of the program4, by CoolStuff.LoadImage.

This pattern is repeated three times, once with each different image that’s created. That shows us that there’s only one call at startup to load all images, and there’s only one place it could come from: CoolStuff.LoadImage. Which means, by induction, every function that calls CoolStuff.LoadImage are the only things that have access to those images5. And whatever calls those functions in turn potentially have second-hand access to the data gathered from CoolStuff.LoadImage.

Where do the Drawings Go?

Okay, so let’s work up now. We have a loaded image. The next piece of the puzzle is the function that calls CoolStuff.LoadImage, and there’s only one relevant call which comes from Drawings:

// Assembly-CSharp, Version=0.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null

// Drawings

using System.IO;

using UnityEngine;

public static Texture2D GetDrawing(int drawingId)

{

Texture2D result = null;

if (!s_loaded[drawingId])

{

if (s_drawings[drawingId] == null)

{

s_drawings[drawingId] = new Texture2D(4, 4, TextureFormat.RGBA32, mipmap: true);

s_drawings[drawingId].name = "Drawing";

}

string path = Path.Combine(saveFilePath, SaveGame.GetDrawingFileName(drawingId));

s_loaded[drawingId] = CoolStuff.LoadImage(path, s_drawings[drawingId]);

if (s_loaded[drawingId])

{

s_drawings[drawingId].name = Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(path);

result = s_drawings[drawingId];

}

}

else

{

result = s_drawings[drawingId];

}

return result;

}Again, to translate: this will load a drawing and then cache that loaded drawing for future uses. Everything that needs drawing data for something will call this function first.

Now, we won’t bore you with the rest of the chain of calling GetDrawing, but if you keep going up the line you will eventually find the functions that Mountain (2014) uses in actual gameplay for drawings.

The groundwork has all been laid, so we’re about to discuss what the drawings actually do. To revisit the points made before: have you locked in an answer as to what version of Mountain (2014) would make you satisfied? Given everything you know about how the game plays, what internals and inner guts could it have that would make it a game for you?

Mountain (2014) has a phrase it loves to repeat. It’s said at the start. It’s said after 1000 hours of play. It’s even written on Mountain (2014)’s official arcade cabinet6.

YOU ARE MOUNTAIN.

YOU ARE GOD.

Does that mean anything to you? Mountain (2014) wants to be mysterious, secretive, enticing. Like any art, it wants to jumpstart your train of thought. And so you have the option to start guessing: “How much of the Mountain comes from me?” “What makes my Mountain unique?” “How am I MOUNTAIN?” “How am I GOD?”. We can easily get wrapped up in the mystery if we allow ourselves to ponder. But Mountain, by its own definition, is a game. A game-like thing, at least. Anyone can claim it to be more than the sum of its parts, but it fundamentally has rules that we can break down and analyze. Mountain is its systems. When we look at what it actually does, what can we see?

What the Drawings Actually Do

Drawing #1

The first drawing is used in Thoughts.WeatherThought. What is that? Sometimes Mountain (2014) will show bits of text on the screen:

It calls these bits of text “thoughts”. And a weather thought is one related to the weather. And based on the in-game hour and season, it will pick a pixel on first drawing the game presented you. If the pixel is black, the thought will be sad. If the pixel is white, the thought will be happy. And so the possible texts that you can see will change based on that7.

Drawing #3

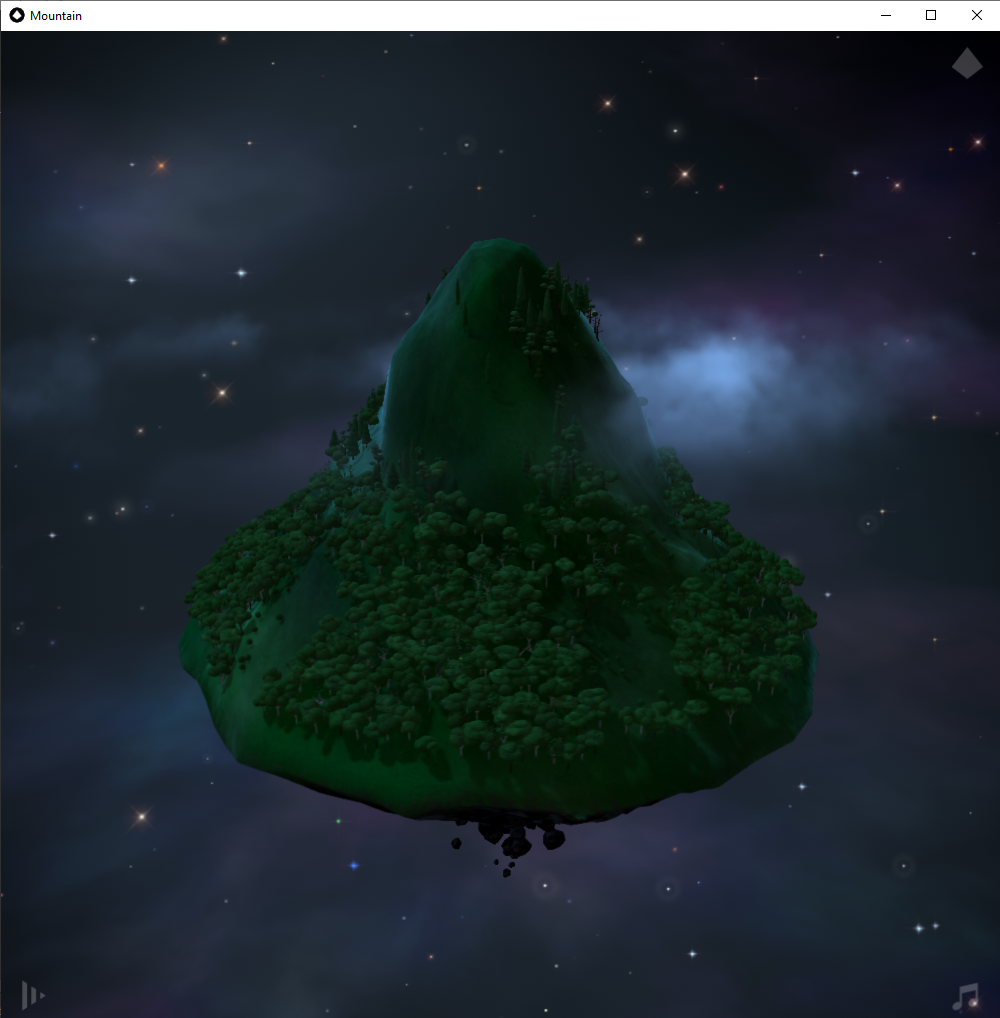

The third drawing is used in both SpaceDebrisManager.SpawnDebris and SpaceDebrisManager.LoadCo.

And sometimes your Mountain from Mountain (2014) will have debris that falls on the Mountain:

And for the relevant functions, they each use exactly the same formula:

/* To simplify, I'm also including the values of DebrisLifetimeHoursMin and DebrisLifetimeHoursMax as part of the code

* (although they're stored elsewhere, and the values are subject to change based on your version of Mountain (2014)):

*/

struct currentPlatform {

float DebrisLifetimeHoursMin = 1f;

float DebrisLifetimeHoursMax = 10f;

}

float lifetime = 3600f * Mathf.Lerp(DebrisLifetimeHoursMin, currentPlatform.DebrisLifetimeHoursMax, Drawings.RandomValue(2));So to discuss this formula, 3600 represents a baseline number of seconds (or a baseline of 1 hour). Mathf.Lerp provides a value between 1 and 10, chosen randomly by the third drawing. Drawings.RandomValue picks a decimal between 0 and 1 by picking 100 random pixels on the third drawing. If the pixel is black, it will add 0.01 to a total. It will then return the total. Then Mathf.Lerp uses that value as a way to interpolate between 1 and 10 hours.

So for instance, a value of 0 from Drawings.RandomValue would mean that lifetime = 1 hour. But a value of 1 from Drawings.RandomValue would mean that lifetime = 10 hours.

So the third drawing determines how long your space debris gets to live for. The more you’ve drawn, the more likely it is that your debris will live longer than an hour.

Drawing #2

This is probably the saddest story of all. Remember that whole debacle with actually READING the drawings? Well uhhh, while the second drawing is indeed read (same as all the rest), there’s a separate function Drawings.GetDrawingFileSize:

// Assembly-CSharp, Version=0.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null

// Drawings

using System;

using System.IO;

using UnityEngine;

public static long GetDrawingFileSize(int drawingId)

{

string text = Path.Combine(saveFilePath, SaveGame.GetDrawingFileName(drawingId));

if (File.Exists(text))

{

try

{

FileInfo fileInfo = new FileInfo(text);

return fileInfo.Length;

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Debug.LogError("Couldn't get file info for " + text + ": " + ex.Message);

}

}

else

{

Debug.Log("There is no file at " + text);

}

return UnityEngine.Random.Range(2000, 23000);

}Which returns the size of the file in bytes. And this function is used in TimeSaver.Start, where TimeSaver is Mountain (2014)’s way of internally tracking how much time has passed. Are you ready? Because here’s the whole formula:

// Assembly-CSharp, Version=0.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null

// TimeSaver

private void Start()

{

if (!SaveGame.IsLoading)

{

Sky.Cycle.Hour = (Hour = World.Settings.NewGameTimeOfDay);

PlatformSpecificSettings currentPlatform = World.Settings.CurrentPlatform;

float dayLengthInMinutesMin = currentPlatform.DayLengthInMinutesMin;

float num = (currentPlatform.DayLengthInMinutesMax - dayLengthInMinutesMin) * 60f;

long drawingFileSize = Drawings.GetDrawingFileSize(1);

DayLengthInMinutes = (Sky.Components.Time.DayLengthInMinutes = dayLengthInMinutesMin + (float)drawingFileSize % num / 60f);

IsLoaded = true;

}

}Let me focus on the important part:

// For clarity, dayLengthInMinutesMin = 6 minutes. But it can depend on your platform.

float dayLengthInMinutesMin = currentPlatform.DayLengthInMinutesMin;

// Same with DayLengthInMinutesMax. The default value is 10 minutes.

// So num is equal to 240 seconds by default.

float num = (currentPlatform.DayLengthInMinutesMax - dayLengthInMinutesMin) * 60f;

long drawingFileSize = Drawings.GetDrawingFileSize(1);

// To parenthesize (at least I hope that's how this is interpreted, otherwise the value would always be 6):

// 6 + ((drawingFileSize % num)/60).

DayLengthInMinutes = (Sky.Components.Time.DayLengthInMinutes = dayLengthInMinutesMin + (float)drawingFileSize % num / 60f);To simplify the formula: the size of your file determines how long your day is in minutes. And there’s no easy correlation between what you’ve drawn and how long your day is, as that % operator takes the modulus of the file size so that the possible value is constrained to be between 0 and num.

That’s it.

Some platforms will skip the drawing entirely and just use random variables, but if you have a drawing, congrats! By a very technical definition of the word “technically”, the drawings do indeed do something to influence Mountain (2014)’s gameplay.

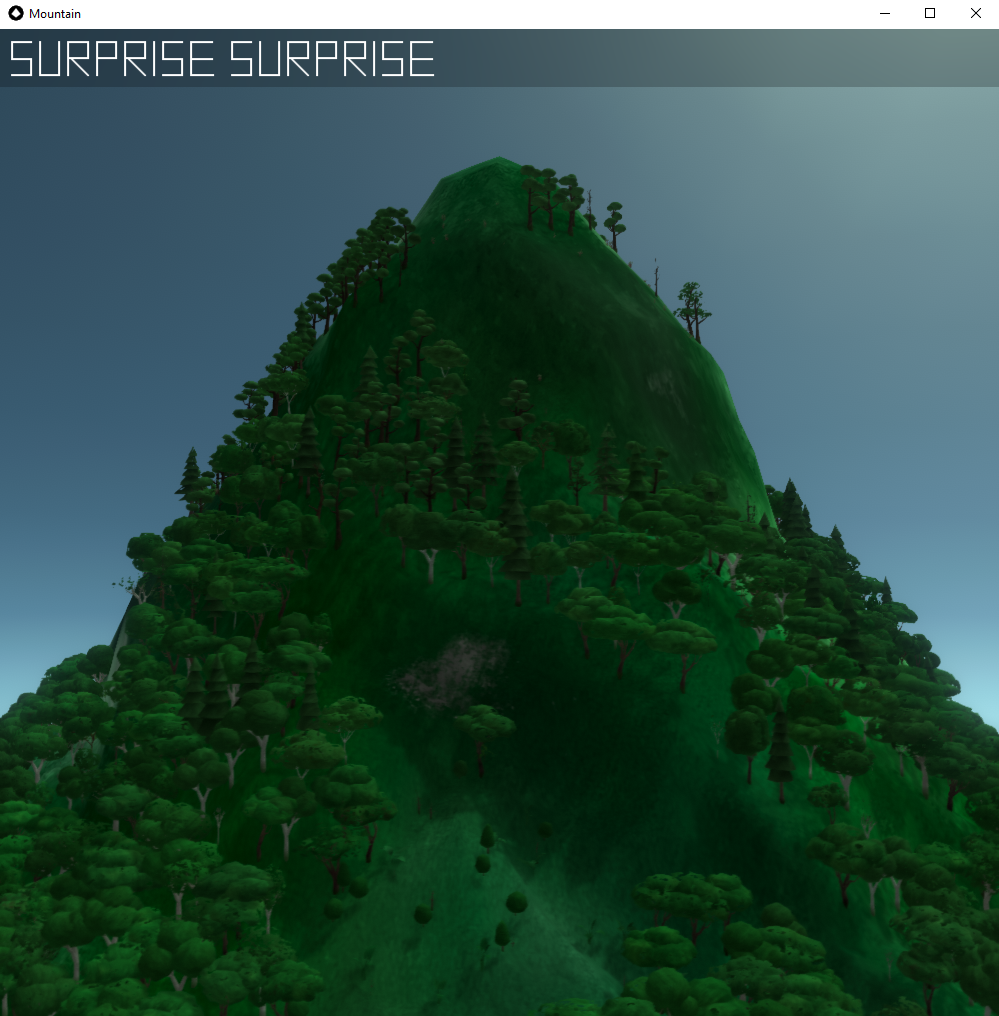

And so here we are. Mountain (2014) connects your drawings to its content with little effort. If it’s a game, there’s not a lot for the player to do. The only constant is the Mountain itself— there’s only one model for the Mountain that is not modified based on any player input. Here it is:

The conclusion we’ll leave it at is this: don’t let a game define itself to you. You have the curiosity and the tools available to you to find meaning for yourself. Definitions be damned - you can learn how your software works. If you have the time and the patience for it, you can break apart the narrative and learn something new.

-

If you’re not on Windows, drawings are stored to Unity’s persistent application data path. If you’re on Apple TV8, it will save to a temporary cache path. ↩

-

In this case, is actually used to EITHER create or open the file. ↩

-

You can look at the Category column for Event Details to see what’s a Metadata Read vs. an actual Read of the file. ↩

-

Checked using ILSpy’s Analysis tool. ↩

-

In the code for Mountain, that is. Fun sidenote: If you delete the files, ProcessMonitor also shows that Steam’s cloud system will re-acquire them as soon as you run Mountain again BEFORE Mountain access the files itself. ↩

-

Yes, Mountain (2014) has an arcade cabinet. ↩

-

Finding what text is written is a whole other matter of hunting through memory for the right values. And so I’ve elected not to. Because finals are in three days as of writing this. ↩